Such were the words of my Spanish professor, words of wisdom passed unto her by her professor before her. After watching the video "Naturally Obsessed" I can see, in a way, what she meant. The way the video portrayed getting your PhD made it seem like there is a lot to be sacrificed. Happiness, relationships, certainty...

We watched as one man, Rob, thought he made an incredible discovery, then discovered his data wasn't what they needed. We watched as a man named Kil told us he and his fiancé were forced to call off their engagement because he didn't have a real job and didn't know if he ever would. We watched as a woman named Gabe quit because she was tired of being completely independent all the time.

Our class sat around and discussed the documentary afterward, but I sat in silence, trying to take it all in, not sure what to say.

A PhD would be nice. But there are so many other things I want to do with my life as well, and I have other people who are important to me that I need to consider. My boyfriend and I have already made sacrifices in our relationship for the sake of education and opportunities. Last January I went to the Galapagos Islands as a conservation volunteer. This January he went to France to work on a documentary. This summer I'm applying to do research and that may take me to Iowa City depending on where I get in. The following spring semester I'm going to Spain. And if we're still together after undergrad, we may be postponing any further steps in our relationship for another two years while I go to get my Masters in Genetic Counseling. The struggles Kil had with his fiancé really freaked me out a bit. Then we saw Rob with his wife, and my own mentor told us she had her first kid in graduate school. So there are successful relationships, but there are still other issues I have with going straight into earning a PhD.

Then I watched Gabe talk about how difficult it was not to know how long you were going to be working towards your PhD, or if you were ever going to find the answer to your question. And that doesn't appeal to me either. I like to have set goals in a situation, knowing when I can expect to finish, having benchmarks and a tangible end to all my work. Doing research doesn't work that way. You never know how long you'll be there, or if your problem is even solvable. It's certainly fun for awhile, and I'm having a good time in my class. But I know that when I graduate with my undergrad degree, the research I will be doing here will be finished.

Research will still be a component as I work for my Masters. Like I stated in a previous post, there is a research career branch in genetic counseling. There is a research component in the curriculum, so the experience I'm getting now will certainly not be going to waste. It's a matter of heading straight down the research path or settling down in a clinical setting.

I'm certainly not ruling out going on to get my PhD at any time in my life. With my current life goals, it just doesn't fit into my young adulthood. I want to earn my Masters, get the job I want, get married, travel, have kids. From the research I've done on my career, a PhD doesn't increase much of the earning potential of a genetic counselor, so I don't even think it would be worth it financially until I was looking for another challenge in my life.

January 19, 2011

January 16, 2011

Becoming an Effective Researcher: Take the Plunge, Make Discoveries, Be Stupid

For class tomorrow we were assigned to do three rather interesting readings that were not scientific, but rather, about the process of scientific research. On the whole, they made me both terrified of going into research permanently, and yet excited about what a lifetime of research could entail.

The first article was one part of two and described what it was like if one were to take the plunge into earning a Ph.D. It gave a bit of advice as to what really makes the graduate program; as it turns out, an excellent mentor is the best thing a graduate student can receive from any program. I am very appreciative of my own mentor, even before entering into this course. She is my academic advisor as well, and I still remember her stopping me in the halls last year during registration time to let me know that the class I had wanted to take, (full at the time) had opened up a new slot. She's pointed me in the direction of scholarships and internship opportunities and was the one who convinced me to take this class. When reading the author's spiel on choosing a mentor, I knew that at least for undergrad, I've got a pretty good one. The chemistry of our lab is a good one as well. People are generally happy and fun, eager to help and chatty. I'm hopeful that, were I to one day pursue a Ph.D., that the conditions would be similar.

The second article was a continuation of Jonathan Yewdell's advice. This gave a more in depth explanation of what it takes to be a good researcher. It takes a natural curiosity, bravura, and self-confidence to carry you through with ideas. It is necessary to be resourceful, to ask questions, and pay scrupulous attention to detail. I don't know if it made me feel better about considering the research path or worse. I feel that in some instances I am completely lacking the self-confidence outlined by the author. Now is one of those times because even though I've been in the lab for two full weeks now, I still realize there are things I need to learn, and I feel like there's so much more I have to learn before I can even fully understand my project. When he talks about asking questions and being curious, I wonder if I really have that curiosity that is so desired. Am I just saying I want to know about certain things because this is something I think I want to do with my life? Or do I really want to know these things? Some days I really feel curious and I'll go on a reading spree, but others days I feel almost tired of it. I suppose assessing my curiosity would be finding the sum of these parts. I wonder often if I have the attention to detail the author dictates. I feel like I do take great care, and I'm obsessive compulsive enough that not much gets through. On the other hand, moments when I forget to write down a temperature in my lab book (as just recently happened) shake me up and make me wonder if I'm just fooling myself.

My favorite article was the third one, and I'm so glad I read it last. Because research has been making me feel pretty stupid, clueless, almost clumsy as I stumble my way through a world that I only know little about. I feel like I'm watching everyone else do exactly what they need to, knowing automatically what has to be done, able to write about these things scientifically off the top of their heads. I keep telling myself it's because I'm new to the lab and these things will come with time and experience. Like I said, this third article made me feel so much better. It said that the point of research was to make you feel stupid, in the ignorant way. I felt so much better when I read "If we don't feel stupid it means we're not really trying." This school year has brought about a lot of self-analysis because of how my entire high school career was based on getting the grade. I had straight A's and was obsessive about maintaining them. I managed to keep my 4.0 through my first year of college, but this fall semester finally brought me to my "breaking point" if you will. I got a B+ in Organic Chemistry and a B in Biostatistics and Experimental Design. It took a lot of introspection to cope, and a lot of self-coaching to keep me from panicking and feeling like my future hopes and dreams were going to fall through. It's hard. I'm not used to not knowing the answers. It's a slow and difficult process, learning to accept the fact that you can't be perfect. In an odd way, I feel like a masochist. I want to be perfect and I want to get perfect grades so I can go on to my perfect life. It still kills me sometimes when I see my 3.85, and not even my boyfriend can understand why I decided to take Organic Chemistry II next semester.

But in away, Science is saving me from myself. It's teaching me it's okay not to know everything, or even not to pretend to know...

I haven't decided if I want to do research permanently. If I had to make a guess as to what I will end up doing, it would be something along the lines of going to get my Masters in Genetic Counseling. Doing that for many years, getting married, having a family. Then with an empty nest and years of experience under my belt, going for a change of scenery and getting a Ph.D.

Also, here is what I was like in high school. I don't know how I had friends, but I did, so thanks guys:

Schwarts, M. A. The importance of stupidity in scientific research. Journal of Cell Science. 9 April 2008

Yewdell, J.W. How to succeed in science: a concise guide for young scientists. Part I: taking the plunge. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10 April 2008

Yewdell, J.W. How to succeed in science: a concise guide for young scientists. Part II: making discoveries. Nature rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10 April 2008

The first article was one part of two and described what it was like if one were to take the plunge into earning a Ph.D. It gave a bit of advice as to what really makes the graduate program; as it turns out, an excellent mentor is the best thing a graduate student can receive from any program. I am very appreciative of my own mentor, even before entering into this course. She is my academic advisor as well, and I still remember her stopping me in the halls last year during registration time to let me know that the class I had wanted to take, (full at the time) had opened up a new slot. She's pointed me in the direction of scholarships and internship opportunities and was the one who convinced me to take this class. When reading the author's spiel on choosing a mentor, I knew that at least for undergrad, I've got a pretty good one. The chemistry of our lab is a good one as well. People are generally happy and fun, eager to help and chatty. I'm hopeful that, were I to one day pursue a Ph.D., that the conditions would be similar.

The second article was a continuation of Jonathan Yewdell's advice. This gave a more in depth explanation of what it takes to be a good researcher. It takes a natural curiosity, bravura, and self-confidence to carry you through with ideas. It is necessary to be resourceful, to ask questions, and pay scrupulous attention to detail. I don't know if it made me feel better about considering the research path or worse. I feel that in some instances I am completely lacking the self-confidence outlined by the author. Now is one of those times because even though I've been in the lab for two full weeks now, I still realize there are things I need to learn, and I feel like there's so much more I have to learn before I can even fully understand my project. When he talks about asking questions and being curious, I wonder if I really have that curiosity that is so desired. Am I just saying I want to know about certain things because this is something I think I want to do with my life? Or do I really want to know these things? Some days I really feel curious and I'll go on a reading spree, but others days I feel almost tired of it. I suppose assessing my curiosity would be finding the sum of these parts. I wonder often if I have the attention to detail the author dictates. I feel like I do take great care, and I'm obsessive compulsive enough that not much gets through. On the other hand, moments when I forget to write down a temperature in my lab book (as just recently happened) shake me up and make me wonder if I'm just fooling myself.

My favorite article was the third one, and I'm so glad I read it last. Because research has been making me feel pretty stupid, clueless, almost clumsy as I stumble my way through a world that I only know little about. I feel like I'm watching everyone else do exactly what they need to, knowing automatically what has to be done, able to write about these things scientifically off the top of their heads. I keep telling myself it's because I'm new to the lab and these things will come with time and experience. Like I said, this third article made me feel so much better. It said that the point of research was to make you feel stupid, in the ignorant way. I felt so much better when I read "If we don't feel stupid it means we're not really trying." This school year has brought about a lot of self-analysis because of how my entire high school career was based on getting the grade. I had straight A's and was obsessive about maintaining them. I managed to keep my 4.0 through my first year of college, but this fall semester finally brought me to my "breaking point" if you will. I got a B+ in Organic Chemistry and a B in Biostatistics and Experimental Design. It took a lot of introspection to cope, and a lot of self-coaching to keep me from panicking and feeling like my future hopes and dreams were going to fall through. It's hard. I'm not used to not knowing the answers. It's a slow and difficult process, learning to accept the fact that you can't be perfect. In an odd way, I feel like a masochist. I want to be perfect and I want to get perfect grades so I can go on to my perfect life. It still kills me sometimes when I see my 3.85, and not even my boyfriend can understand why I decided to take Organic Chemistry II next semester.

But in away, Science is saving me from myself. It's teaching me it's okay not to know everything, or even not to pretend to know...

I haven't decided if I want to do research permanently. If I had to make a guess as to what I will end up doing, it would be something along the lines of going to get my Masters in Genetic Counseling. Doing that for many years, getting married, having a family. Then with an empty nest and years of experience under my belt, going for a change of scenery and getting a Ph.D.

Also, here is what I was like in high school. I don't know how I had friends, but I did, so thanks guys:

Literature Cited

Schwarts, M. A. The importance of stupidity in scientific research. Journal of Cell Science. 9 April 2008

Yewdell, J.W. How to succeed in science: a concise guide for young scientists. Part I: taking the plunge. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10 April 2008

Yewdell, J.W. How to succeed in science: a concise guide for young scientists. Part II: making discoveries. Nature rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10 April 2008

January 14, 2011

Shadowing Experiences

So for our class we were supposed to take around 30 minutes or so to follow somebody else around while they worked on their project. The goal was to make them feel extremely nervous and to judge their every move, as well as possibly learn something new.

I was lucky enough to shadow Ty, a senior in the lab, who was very instructive when things were going well in the first 10 minutes of me observing him. His project involves inserting a ligation-independent cloning vector in from a plasmid. I have yet to take Genetics, and it only partially makes sense to me so I apologize if I have difficulty putting it into layman terms. I know many of you reading this blog are not biologists, or even scientists (Hi Mom). Basically, he's taking plasmid DNA (circular DNA), cutting it in a certain place that will leave appropriate overhangs to be pieced together like a puzzle. This piece is the "ligation independent cloning vector." I may be wrong, and if so I apologize. It's a delicate process that involves using appropriate enzymes to cut in the appropriate places to fit the appropriate piece of DNA to make the appropriate cloned sequence. You can read Ty's blog here.

I was very lucky to shadow him for a few reasons. Like I said, he was very instructive and he shares high seniority. One unexpected benefit to shadowing Ty was how things did not go well while I observed him. After 10 minutes he realized he was missing the appropriate concentration of a certain chemical he needed. The next 20 minutes were him and our mentor frustratingly trying to figure out how on earth they could make enough of the necessary concentration with their limited supply, beating themselves over the head for not checking and ordering some ahead of time. While Ty was frustrated and apologized repeatedly for my boring shadow experience, I'm actually really relieved that I got to see an upperclassman run into problems. It was comforting in a way, actually. I'm new to the whole lab experience and at times make novice mistakes that reveal my n00b status.

I was lucky enough to shadow Ty, a senior in the lab, who was very instructive when things were going well in the first 10 minutes of me observing him. His project involves inserting a ligation-independent cloning vector in from a plasmid. I have yet to take Genetics, and it only partially makes sense to me so I apologize if I have difficulty putting it into layman terms. I know many of you reading this blog are not biologists, or even scientists (Hi Mom). Basically, he's taking plasmid DNA (circular DNA), cutting it in a certain place that will leave appropriate overhangs to be pieced together like a puzzle. This piece is the "ligation independent cloning vector." I may be wrong, and if so I apologize. It's a delicate process that involves using appropriate enzymes to cut in the appropriate places to fit the appropriate piece of DNA to make the appropriate cloned sequence. You can read Ty's blog here.

I was very lucky to shadow him for a few reasons. Like I said, he was very instructive and he shares high seniority. One unexpected benefit to shadowing Ty was how things did not go well while I observed him. After 10 minutes he realized he was missing the appropriate concentration of a certain chemical he needed. The next 20 minutes were him and our mentor frustratingly trying to figure out how on earth they could make enough of the necessary concentration with their limited supply, beating themselves over the head for not checking and ordering some ahead of time. While Ty was frustrated and apologized repeatedly for my boring shadow experience, I'm actually really relieved that I got to see an upperclassman run into problems. It was comforting in a way, actually. I'm new to the whole lab experience and at times make novice mistakes that reveal my n00b status.

But Ty made me feel a little better about my situation. Even the best of us at times make mistakes, and it is frustrating. And if I decide to go into research, it will continue to be frustrating, as mistakes will continue to be made (though preferably in smaller and smaller amounts). Something to look forward to, and I don't mean that sarcastically (well, mostly). The challenge is part of the adventure that is science.

January 12, 2011

Research: Then and Now

And by "then" I mean me before this class and by "now" I mean me in this class.

There are some significant changes in my opinion. I feel that before I knew the value of undergraduate research before, which I decided to at least tentatively major in Biological Research. It was something I was interested in trying, but I was very nervous going into. For one, I didn't have any idea what I wanted to research and that was something that originally turned me off from the prospect. Honestly, it was like I was a 5th grader again, moving to my new school, sick to my stomach because I thought it was going to be all stuff I didn't know and I was going to be completely lost and no one would help me. It was entirely irrational, of course.

For one, I was very grateful to be presented with an initial idea to pursue. It took a lot of creative pressure off (because seriously--when you have all of history's accumulated Biological Knowledge at your fingertips, it's hard to reach in and pull out a single, specific idea to pursue). Aside from that, I've had a lot of guidance in starting up this process which is something I really needed because I don't take Genetics until next semester. I'm learning kinetically which is new for me, but I'm enjoying the process. Research is quite a bit more fun than I expected. I thought it would be more like this:

There are some significant changes in my opinion. I feel that before I knew the value of undergraduate research before, which I decided to at least tentatively major in Biological Research. It was something I was interested in trying, but I was very nervous going into. For one, I didn't have any idea what I wanted to research and that was something that originally turned me off from the prospect. Honestly, it was like I was a 5th grader again, moving to my new school, sick to my stomach because I thought it was going to be all stuff I didn't know and I was going to be completely lost and no one would help me. It was entirely irrational, of course.

For one, I was very grateful to be presented with an initial idea to pursue. It took a lot of creative pressure off (because seriously--when you have all of history's accumulated Biological Knowledge at your fingertips, it's hard to reach in and pull out a single, specific idea to pursue). Aside from that, I've had a lot of guidance in starting up this process which is something I really needed because I don't take Genetics until next semester. I'm learning kinetically which is new for me, but I'm enjoying the process. Research is quite a bit more fun than I expected. I thought it would be more like this:

But it's actually more like this:

Me and My Cat

I don't actually have my cat in here while I'm working, nor do I even have my cat at school, but if you want to quibble over details, the cat is a visual metaphor for how fun being in a lab for seven hours every day can be.

Why major in Biological Research if I'm going into genetic counseling? Because. There are two main branches to the field--clinical and research. I certainly want to give clinical a try because I feel that's where my passion lies. My Public Speaking professor last year told me she hoped I didn't work in a lab for too long because I am a very good public speaker and she wants to see me with people. But I don't have any qualms about going into research or even one day pursuing a PhD.

Why major in Biological Research if I'm going into genetic counseling? Because. There are two main branches to the field--clinical and research. I certainly want to give clinical a try because I feel that's where my passion lies. My Public Speaking professor last year told me she hoped I didn't work in a lab for too long because I am a very good public speaker and she wants to see me with people. But I don't have any qualms about going into research or even one day pursuing a PhD.

January 10, 2011

Why Genetic Counseling?

It is the obligatory question. It comes after "Where do you go to school?", "What are you studying?", "What do you want to be?", and "Ooh, is that when parents go in and ask for a blue eyed baby girl and you make it?" Followed by face-palm.

Genetic counseling involves many things, but here's a summary. A genetic counselor is someone who works as a patient advocate on a health care team.They serve as a resource for health care professionals as well as the general public. They see a variety of clients, but many specialize in one of the various categories such as prenatal, postnatal, or adult onset diseases (such as Huntington's Disease). They generally work in hospitals though some have their own private practice. They are concerned with the emotional well-being of their clients, processing the complicated and convoluted issue of genetic disease and dealing with the tangled web of emotions that comes with it. They are educators. They are advocates. They are a support system.

They are not:

- Genetic Engineers

- Gene Therapists

- Cloners

- Doctors (and by doctor I mean physician, as some genetic counselors do hold doctorates and would therefore be considered doctors)

Now why on earth would I want to participate in this profession? Aside from it's obvious awesome-ness, I can count at least five compelling, personal motivations off the top of my head. I will leach them out slowly in future blog posts, but what follows this paragraph was my first indication that I could do this profession, and even be passionate about it. I wear a bracelet on my wrist every day as a reminder of my goal.

My cousin is a pretty cool kid. He loves sports and he will turn anything into a competition. And even though at times he's too cool for hugs and kisses from his older cousins, I still love the little guy. He's turning eight soon, which is hard to believe. He has a genetic disorder by the name of Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. My mom and my sister are carriers. My cousin's family have done their homework and they know a lot about the situation; they're also active in fundraisers and awareness projects. I gave a link to a lengthy explanation of the disorder, but in brief, the disease is characterized by lung disease (usually emphysema) and sometimes liver disease. Onset is usually around age 40, though of course there is a range; some people live normal lives completely unaware of their condition. Those with the most severe deficiency may die in infancy.

So when my family was discovering all this stuff for the first time there was a lot of uncertainty. There were a lot of questions raised over the years. I answered a lot of them for my own immediate family because I was the only one who knew how to make a Punnett square. I remember specifically showing my mom the inheritance pattern for my cousin. When I became really interested in genetics (about sophomore year of high school) I made presentations for a Public Speaking class as well as a Child Development class about the pros and cons of genetic testing, using my cousin as an example. I made a video that was gossiped about quite a bit in school because it made a few of the girls in my class tear up.

I remember going in to be tested for Alpha-1. I remember what wondering feels like. I remember my sister's reaction when she found out she was a carrier. I've lived (at least part) of the client's experience on one side of the desk. And I want to see the other.

Genetic counseling involves many things, but here's a summary. A genetic counselor is someone who works as a patient advocate on a health care team.They serve as a resource for health care professionals as well as the general public. They see a variety of clients, but many specialize in one of the various categories such as prenatal, postnatal, or adult onset diseases (such as Huntington's Disease). They generally work in hospitals though some have their own private practice. They are concerned with the emotional well-being of their clients, processing the complicated and convoluted issue of genetic disease and dealing with the tangled web of emotions that comes with it. They are educators. They are advocates. They are a support system.

They are not:

- Genetic Engineers

- Gene Therapists

- Cloners

- Doctors (and by doctor I mean physician, as some genetic counselors do hold doctorates and would therefore be considered doctors)

Now why on earth would I want to participate in this profession? Aside from it's obvious awesome-ness, I can count at least five compelling, personal motivations off the top of my head. I will leach them out slowly in future blog posts, but what follows this paragraph was my first indication that I could do this profession, and even be passionate about it. I wear a bracelet on my wrist every day as a reminder of my goal.

My cousin is a pretty cool kid. He loves sports and he will turn anything into a competition. And even though at times he's too cool for hugs and kisses from his older cousins, I still love the little guy. He's turning eight soon, which is hard to believe. He has a genetic disorder by the name of Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. My mom and my sister are carriers. My cousin's family have done their homework and they know a lot about the situation; they're also active in fundraisers and awareness projects. I gave a link to a lengthy explanation of the disorder, but in brief, the disease is characterized by lung disease (usually emphysema) and sometimes liver disease. Onset is usually around age 40, though of course there is a range; some people live normal lives completely unaware of their condition. Those with the most severe deficiency may die in infancy.

So when my family was discovering all this stuff for the first time there was a lot of uncertainty. There were a lot of questions raised over the years. I answered a lot of them for my own immediate family because I was the only one who knew how to make a Punnett square. I remember specifically showing my mom the inheritance pattern for my cousin. When I became really interested in genetics (about sophomore year of high school) I made presentations for a Public Speaking class as well as a Child Development class about the pros and cons of genetic testing, using my cousin as an example. I made a video that was gossiped about quite a bit in school because it made a few of the girls in my class tear up.

I remember going in to be tested for Alpha-1. I remember what wondering feels like. I remember my sister's reaction when she found out she was a carrier. I've lived (at least part) of the client's experience on one side of the desk. And I want to see the other.

January 6, 2011

Isolating DNA - Much Harder than it Looks on TV

A lot has been done this week, though there isn't really much to show for it. Who knew DNA isolation was a trial-and-error process? The best thing that happened this week was getting to pluck my eyebrows for science. The worst was... well, I'll think of something.

We're following a rough protocol for DNA isolation from human hair and it took a lot of research to find something mildly promising. These "recipes," if you will, appear highly guarded; most instructions involve the purchasing of a kit which contains a mysterious patented variety of solutions. However, my mentor and myself managed to find some instructions for creating a buffer solution to dissolve the eyebrow hairs. There is also a protocol for the isolation of DNA using phenol-chloroform, but we haven't gotten to that step yet because we were out of phenol-chloroform and had to prepare our own.

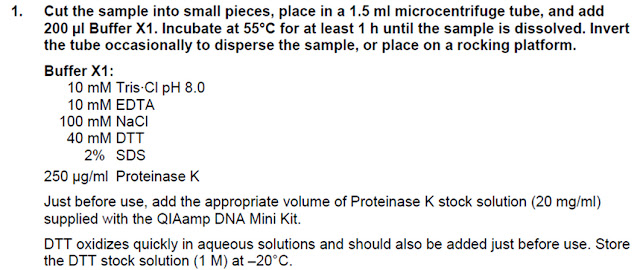

Instructions:

There are some tips I've discovered in my search for an appropriate method:

* If you don't have to use hair, don't. From the material I've read, it's extremely difficult to get usable DNA from hair samples. If you have to use it, use eyebrow hair and make sure it hurts when you pluck because then you're more likely to have the necessary skin tag at the bottom of the hair.

* Get a kit, or buy already prepared phenol-chloroform. It is a long, time-consuming process that involves highly toxic substances, namely, phenol and chloroform. My mentor and myself enjoy living on the edge, so we're making it ourselves, but we don't know if it has even worked yet because our first attempt failed and we haven't completed the DNA isolation yet; the phenol we had thawed was a pinkish/orange which means it is no good.

On another note, I'm sure many of you are curious about what exactly Epidermolysis Bullosa Simplex is. I will be explaining in my presentation tomorrow, but I can give a brief overview. In summary, it is a genetic disease characterized by fragility of the skin and blistering; severity varies among the four most common phenotypes, as well as between family members. It is usually inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern and is most commonly caused by mutations in the genes KRT14 and KRT5, both responsible for making different forms of keratin. This molecule is important for the functioning of the cytoskeleton. When it isn't working properly, the epidermis and the dermis separate, hence the blistering. There is a website below that I've found very helpful; there's even a section with information specific to genetic counselors.

There are also some pretty interesting (if not gruesome) pictures of those afflicted. If you are in the least bit squeamish, I do not recommend clicking on the links. Some pictures are of babies, as some phenotypes manifest at birth. I'll be using these photos in a presentation tomorrow but they can also be found below:

January 5, 2011

The Hypothesis

We read an article for class on Tuesday, entitled "A Brief History of the Hypothesis." It was an interesting piece of information that discussed the evolution of the word, its uses as opposed to a model, and the use of a question instead of a hypothesis.

I've known the word hypothesis since probably around third grade, and it's been drilled into my head in every science class ever since. This article spent a considerable amount of time discussing the critiques of deductive reasoning and the use of a hypothesis; it also defended inductive reasoning against its philosophical critics.

I have my own musings on the subject. While hypotheses are valuable and at times provide a helpful outline for research I remember becoming frustrated throughout my years of study by their restrictions. Many times I was just curious about a subject. I had questions that I wanted to investigate but because I was bound to a curriculum that was bound to deductive reasoning, I wasn't able to pursue any answers. I had to make an educated guess, a hypothesis, and construct a confined experiment that would answer my narrowly formulated idea. The hypothesis would fail and I would have to start over with nowhere to go. And I'm not even talking about the research I'm doing now; I mean I remember being in 4th grade, trying to come up with a hypothesis for what would happen when 3 different colored liquids were poured into a beaker. I would have been a much less frustrated 9-year-old if I'd been able to just take the liquids and try different things just to see and explore.

That's what I like and prefer about inductive reasoning, the use of a model, and the asking of a question. It may not be philosophically appropriate to assume that what has always happened in the past will always happen in the future, but it's certainly practical. If we assumed we could never know what has happened today will happen tomorrow, there would be chaos and the entire human experience of learning would be disrupted. Inductive reasoning may not be philosophically sound, but it's by far more fun. It's the scientific method kids use when they're exploring something new for the first time. It's the reason I love science--the expedition.

My current project is an expedition into the human genome to see if there's anything new to discover (which is a silly assertion because there's always something new to discover in genetics; don't ever let me get on the subject of epigenetics because I will not stop talking).

I've known the word hypothesis since probably around third grade, and it's been drilled into my head in every science class ever since. This article spent a considerable amount of time discussing the critiques of deductive reasoning and the use of a hypothesis; it also defended inductive reasoning against its philosophical critics.

I have my own musings on the subject. While hypotheses are valuable and at times provide a helpful outline for research I remember becoming frustrated throughout my years of study by their restrictions. Many times I was just curious about a subject. I had questions that I wanted to investigate but because I was bound to a curriculum that was bound to deductive reasoning, I wasn't able to pursue any answers. I had to make an educated guess, a hypothesis, and construct a confined experiment that would answer my narrowly formulated idea. The hypothesis would fail and I would have to start over with nowhere to go. And I'm not even talking about the research I'm doing now; I mean I remember being in 4th grade, trying to come up with a hypothesis for what would happen when 3 different colored liquids were poured into a beaker. I would have been a much less frustrated 9-year-old if I'd been able to just take the liquids and try different things just to see and explore.

That's what I like and prefer about inductive reasoning, the use of a model, and the asking of a question. It may not be philosophically appropriate to assume that what has always happened in the past will always happen in the future, but it's certainly practical. If we assumed we could never know what has happened today will happen tomorrow, there would be chaos and the entire human experience of learning would be disrupted. Inductive reasoning may not be philosophically sound, but it's by far more fun. It's the scientific method kids use when they're exploring something new for the first time. It's the reason I love science--the expedition.

My current project is an expedition into the human genome to see if there's anything new to discover (which is a silly assertion because there's always something new to discover in genetics; don't ever let me get on the subject of epigenetics because I will not stop talking).

January 3, 2011

Insert Genetics Pun Here

There are two reasons I started this blog.

1) It's required (and graded!). I'm spending this month researching Epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS) as part of a research course. The class is serving many purposes. For one, it's supposed to represent the graduate school experience, with 35 hours every week spent in the lab. Also, I may possibly have a Junior and Senior Seminar paper in the works based on how this research goes. And it's fun. Exhibit A: I finished my first seven hour day already and it only felt like two hours, which I suppose is a good sign because I easily spent five hours just trying to figure out an appropriate primer. Exhibit B: THIS COMIC.

1) It's required (and graded!). I'm spending this month researching Epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS) as part of a research course. The class is serving many purposes. For one, it's supposed to represent the graduate school experience, with 35 hours every week spent in the lab. Also, I may possibly have a Junior and Senior Seminar paper in the works based on how this research goes. And it's fun. Exhibit A: I finished my first seven hour day already and it only felt like two hours, which I suppose is a good sign because I easily spent five hours just trying to figure out an appropriate primer. Exhibit B: THIS COMIC.

Wasn't that hilarious? I thought it was hilarious. The lady is a genetic counselor. Which leads me to my second reason for starting this blog.

2) I want to be a genetic counselor, and am terrified about getting into graduate school. I had contemplated making a blog a year or so ago. I decided it would chronicle the careful cultivation of my hopes and dreams, and then chart their sudden crash and the years of travesty that would inevitably follow. Or, maybe, this blog will be discovered by front Page Yahoo! News or the AP and then I will have job offers and scholarships falling out of the sky. My dreams are in the title; I want to get into a graduate school program that only admits five people every year.

There are many good, juicy reasons for me wanting to be a genetic counselor to be confessed at a later date amongst monologues on my research. This class got me up at 7:30 this morning after a Christmas break of afternoon naps.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)